Vocabulary Grid is part eight in an eight-part series on e-learning technical vocabulary systems. Read part one, part two, part three, part four, part five, part six and part seven.

Explore relationships.

This eight-part vocabulary series has focused on meaningful ways to deepen student understanding of technical vocabulary. With careful planning and creative lesson designs, you can create multiple opportunities for students to talk productively with one another. Encourage students to drive their own learning by recalling terms from earlier lessons, preventing a natural forgetting curve. Note: Each activity can be adapted to suit instruction in traditional and blended learning environments.

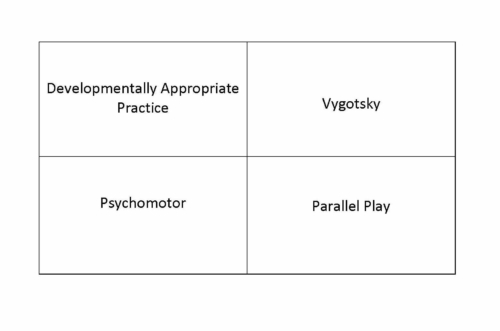

Our final vocabulary lesson provides opportunities for critical thinking and deep follow-up discussion among students. The vocabulary grid challenges students to think through terms and processes where several terms fall into more than one category. Further, after completing the grid, students rationalize and justify their choices — getting to the essence of critical thinking.

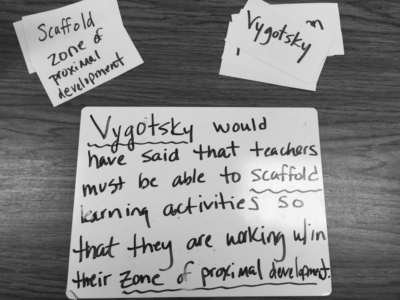

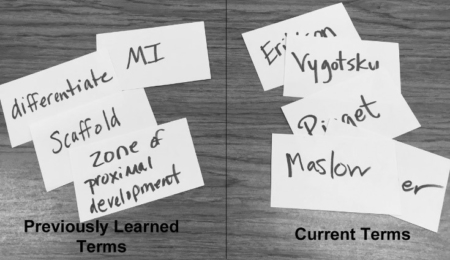

Students develop a more complex understanding of vocabulary words by thinking about how they relate to one another. Do this informally by calling attention to connections during class discussion. You can also add specific activities for this purpose. Graphic organizers like the attached vocabulary grid are especially helpful for defining word relationships.

Vocabulary Grid

Gist: Students record vocabulary terms in categories as they read technical text or work in the lab.

When to use: During reading of manuals, software, or other text. Or bring into the lab with clipboards.

How it works

- Chunk the text into (X) number of groups and group your students into (X) number of groups. Assign each group a portion of text.

- Before reading begins, call students’ attention to the categories on the grid so they know what to look for as they read:

- Describes software or machinery

- Indicates an action

- Describes steps of operation

- Indicates ways to use software or machinery

- Predicts a successful ending of use of software or machinery

- Describes troubleshooting actions

- Each student group reads their portion of text, filling in their grid together.

- There may be overlap or ambiguity about which category a term fits into. Encourage students to discuss this ambiguity. If they can articulate a reason why the term fits into more than one category, they should write it in both. The key is that they must verbalize their reasoning.

Twist

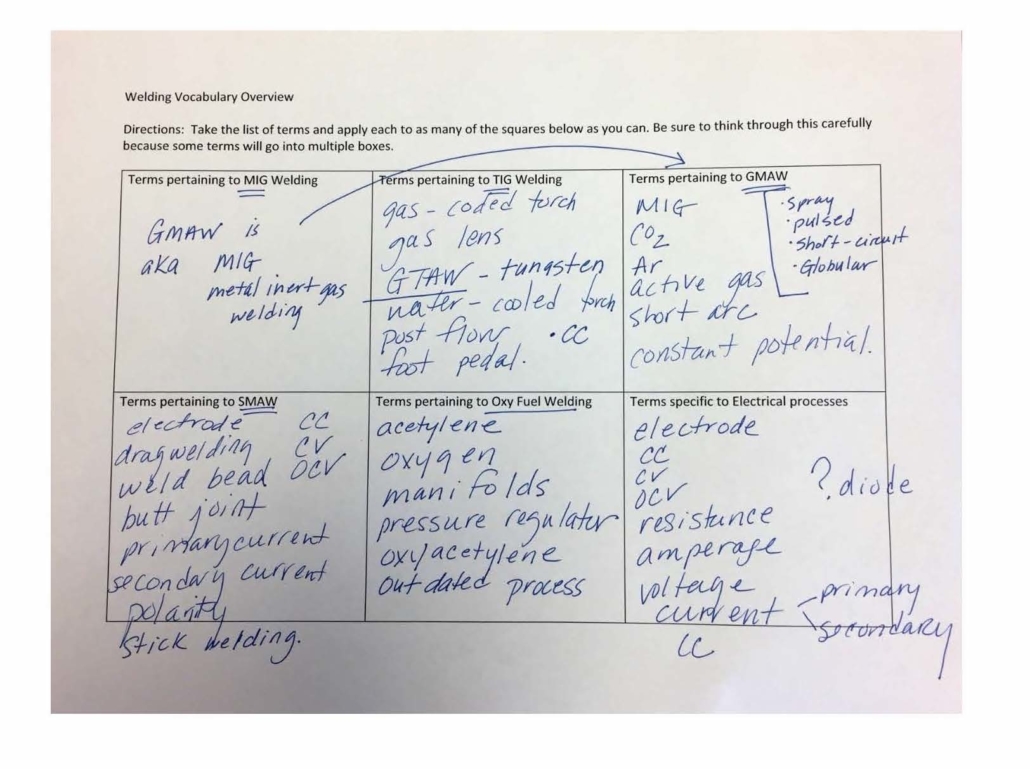

Assign each group a separate category and instruct them to fill in as many terms as possible for that one box. Then have each group share their results with the class.

Tip

Scaffold for students who need additional support by giving them a copy of the chart that is partially filled in. For students needing the highest level of support, fill in the entire grid and ask them to point out terms as they read them.

See the strategy in action.

Download the vocabulary grid for use in your CTE classes. (Note: This sample was created for use in a welding class but can be customized to suit other fields.)

Sandra Adams is a teacher and instructional coach with the Career Academy, Fort Wayne Community Schools. She co-wrote the ACTE-supported book But I’m NOT a Reading Teacher!: Literacy Strategies for Career and Technical Educators with Gwendolyn Leininger, where further detailed explanations of the strategies in this series can be found. Email her.