All tests contain error variance, which means that inaccuracies will exist based on multiple factors, some of which are controllable while others are not. But there are several strategies available to increase the efficacy of a test. In this article we seek to provide some tips and techniques to help improve your assessments.

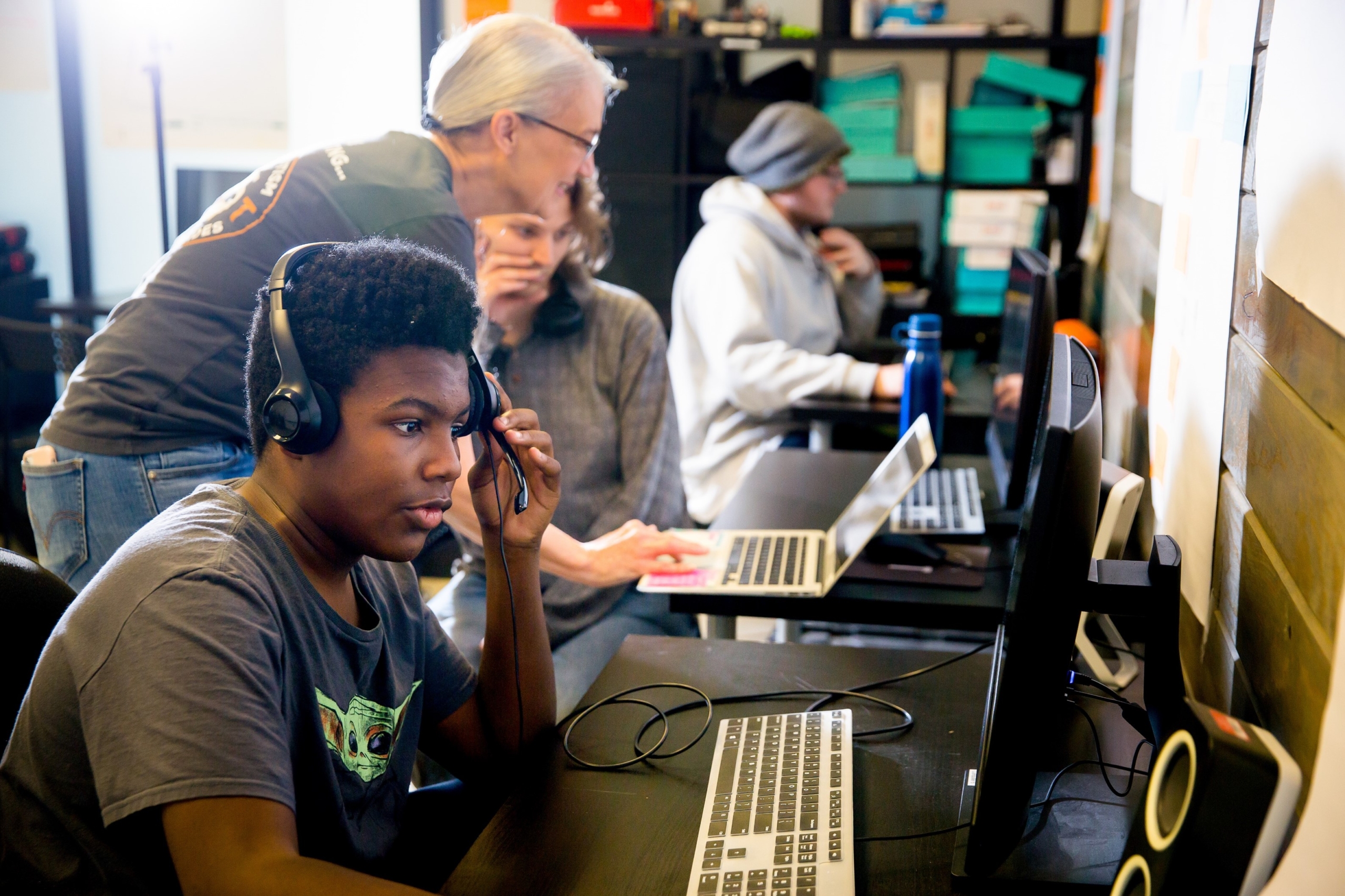

Teachers of high-quality CTE programs recognize the value of analyzing student progress to adjust and improve instruction.

Regardless of the types of testing used, assessment in CTE is based on standards and competencies identified as needed within a specific industry. The most important part of any test (as well as instruction) is to be sure that you are teaching and measuring current concepts and skills. Tests must align closely with what is being taught, and what is being taught should align closely with what students will be expected to know and do in their chosen fields.

1. Determine the scope of the test.

What should be tested or measured? The assessment’s scope will be different based on the purpose of the test and the material taught. Is it a pop quiz, a hands-on exercise, an end-of-unit assessment, an end-of-course assessment? For MC tests, the scope also depends on factors such as preferred length. Most tests in a classroom environment need to be short enough to be administered within one classroom period.

2. Write a test that is fair.

CTE student populations are usually from diverse ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds, and these characteristics should be accounted for in the test design. Consider disability or language access, for example. Figure 1 offers some suggestions for writing better test questions.

[pdf-embedder url=”https://www.acteonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Better-Test_-handout_-Techniques.pdf” title=”Better Test_ handout_ Techniques”]

Rigor is an important aspect in test development.

Include various levels of item difficulty. Some require a student to identify or recall knowledge, while others test their understanding of the process or application, and others ask them to apply knowledge. Here are examples of three levels of rigor pertaining to voltmeters:

- “From the four meters shown, identify the voltmeter…”

- “The proper way to attach the voltmeter to the battery is…”

- “If a voltmeter reads 13.2 volts, this means that the battery is…”

Mix modalities whenever possible.

Multiple choice (MC) questions are the most common test item type, often used to assess a learner’s knowledge of factual information. And they are relatively easy to grade, making them useful for a teacher’s busy schedule. But CTE educators and students often prefer performance-based assessments. There are a few ways you can combine both performance and MC when it comes to testing. For example, teachers can create performance-based MC items on technical content by creating graphics with basic editing tools.

Evaluate the effectiveness.

Analyzing assessment data is a critical part of teaching and learning in any classroom. Data delivers a snapshot of what students know, what students should know, and what students do not know yet. But that

data must be based on strong and accurate measurements. Consider the following when seeking to make

improvements.

- Percent correct: This refers to the number of students who chose the correct answer. If a number is very low, it may be a legitimately difficult item or test. But it’s also possible that something needs to be changed. Is the correct answer actually correct? Are any of the wrong answers also correct? Is the question written in a confusing way?

- Wrong answers: Attractive distractors (or wrong options) can also be an issue. If a lot of students are picking the same wrong answer for an item, it’s important to consider why. Was the wrong answer partially correct? Was it a good distractor for a legitimate reason?

By implementing even just a few of these strategies, test design, delivery and analysis can be improved. Ultimately, these strategies inform teaching and can improve content delivery in the long term.

John Foster, Ph.D., is the retired president and CEO of NOCTI and Nocti Business Solutions.

Patricia Kelley, Ph.D., is an industrial organizational psychologist at NOCTI.

Tina Koepf, Ph.D., is a psychometrician for Nocti Business Solutions.