In an effort to deliver more engaging professional development, Northwest Education Services Career Tech began using the practice of instructional rounds (City et al., 2009). We gave teachers the opportunity to watch one another teach and engage in intentional reflection. And they have become the voice of their own professional learning.

Design engaging professional development.

We began our journey in instructional rounds by speaking with administrators who were also using rounds in their buildings and districts. They were able to give us insight into the benefits and challenges of using rounds at the building level instead of at the district level. While instructional rounds began as a way for a group of instructional leaders to observe classrooms across multiple buildings, we have shifted our gaze to allow for 36 teachers to visit three classrooms each month; we then use the evidence collected by the teachers to debrief and determine the scope of future professional development offerings.

Note: Central to the success of instructional rounds is the idea that they are non-evaluative.

Observers enter classrooms to note what they see and hear, not what is missing. We like to tell our visitors that they are the learners, not the experts. This mindset shift allows participants to look down, not up. We want classroom visitors to watch what the students are doing and being asked to do rather than what the teacher is or is not doing. This guidance reinforces the non-evaluative nature of rounds and makes it possible for administrators to gain a clearer, more holistic view of areas for improvement — which is what the researchers and creators of rounds call our “problem of practice.”

Consider the logistics of instructional rounds.

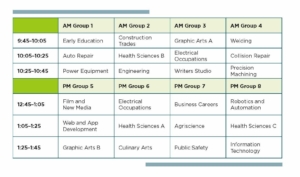

Teachers improve when they watch others teach. We knew the theory was great. But the logistics were the first real challenge. We needed to get 36 teachers into three classrooms each without causing substantial disruptions to students’ learning. We knew that we had one major advantage that would help us implement rounds: Nearly all of our courses are led by a teacher er and a paraprofessional who is also certified as a substitute teacher. This meant that most teachers could leave their classrooms for three 20-minute peer observations while the paraprofessional continued to support instruction. This allowed us to schedule all classroom visits on the same day, scheduled in two one-hour blocks.

Round, debrief, then round again.

We focus our efforts on teachers using competency-based grading to inform their instruction. Thus, we drafted our first problem of practice based on the associated challenges.

- How do students know the quality of their work?

- How do students know how to improve their work?

- And how do teachers use competency-based grading to guide their instruction?

Teachers focused on collecting evidence related to our problem of practice. Then, during morning PD sessions, administrators led teachers through a debriefing protocol that used aspects from City et al.’s work as well as modifications to fit the unique needs of our work in a CTE setting. Specifically, debriefing peer observations could take hours. But we had 60 minutes. So, we asked each teacher to spotlight six pieces of evidence from their classroom visits and use that evidence in small groups.

Teachers took note of patterns, made predictions about professional learning that would impact instruction positively, and then determined what they needed from instructional leadership to achieve their next level of work. They needed specific examples of how to group students using data. And about how to develop processes that students could use to revise their knowledge. From this came the topic for our next session of professional learning.

Here, we see that the practice of instructional rounds never ends. Instead, one enactment of rounds leads to new work, which leads to a new problem of practice.

What are the processes that students use to collect feedback?

What do students do to improve their work after receiving feedback?

Data needs to be collected and used to group students based on their needs.

The first two questions in our original problem of practice didn’t quite hit the underlying idea of competency-based grading. Students need to collect various forms of feedback in order to understand where they are, where they are going and how to get there. In the multiple PD sessions that followed, teachers engaged in rich practice and discussion.

How’s it working? What’s next?

The organization of instructional rounds is, of course, unique to each building. We took the original research from City et al., kept what worked for our building and eliminated things that didn’t fit our culture. We don’t claim to be the paragon of instructional rounds, nor do we think we have perfected it even for ourselves. Constantly, we are tweaking our processes and making deliberate changes to meet the changing needs of our teachers.

No matter what it may look like in your school, the point remains. When teachers gain opportunities to watch other teachers, ideas will be shared. We have seen three positive effects of instructional rounds at our school.

- Increased collaboration

- Increased peer support

- Higher levels of engagement

But this is only the start of our work. Today, we have completed four iterations of building-wide rounds. And our current problem of practice asks, What processes are in place that allow students to revise their knowledge? What kind of data is collected, and how is it used to group and regroup students? What does it look like when a student is engaged and challenged on a daily basis? As we plan, we reflect and ask ourselves challenging questions that foster growth.

Matt Griesinger is an assistant principal at Northwest Education Services Career Tech in Traverse City, Michigan. He holds a bachelor’s degree in integrated language arts education, a master’s degree in curriculum and instruction, and an Ed.S. in educational leadership. Prior to his current role, he was a high school English teacher and a middle school assistant principal.